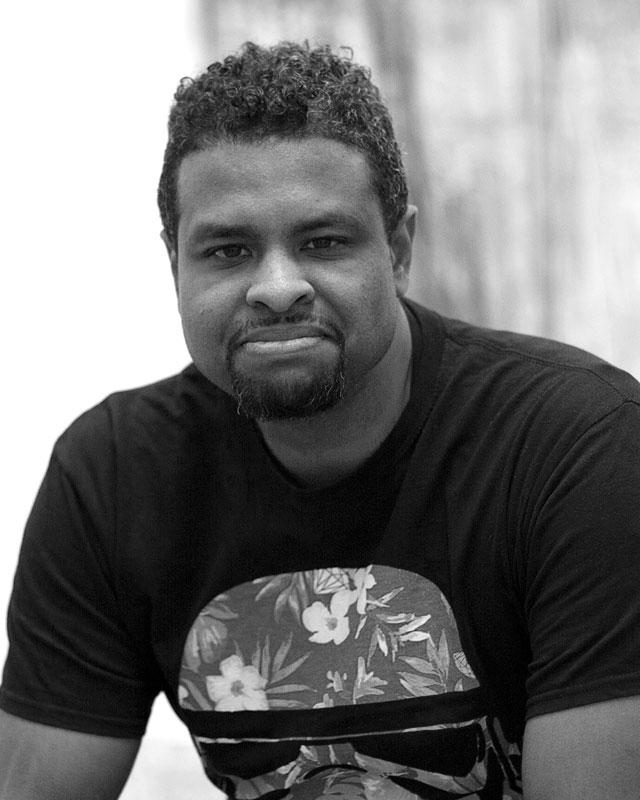

Faheem Majeed (b. 1976) is a Chicago-based artist whose studio practice focuses on investigating, challenging, and highlighting the significance of culturally specific institutions. As its former Executive Director (2007-2011), Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center serves as his primary muse.

Majeed is a recipient of the Field and MacArthur Foundation’s Leaders for a New Chicago Award (2020), the Joyce Foundation Award (2020), the Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Grant (2015), and is a Harpo Foundation Awardee (2016). Majeed’s solo exhibitions include MCA Chicago, SMFA at Tufts, and the Hyde Park Art Center.

I’m a husband, then a father, then a member of my community and then an artist.

In this context I don’t consider “artist” last as much as I consider it at the top of a pyramid whose base consists of the other labels. My art is my voice that allows me to express the interactions that result from my life.

I find that I am drawn to odd or broken things…that translates to both objects and people. I think I’m drawn to these kinds of things because of a bottomless curiosity…not necessarily to tear things apart to see how they work but to understand connections and motivations.

I believe in meeting people where they are…sometimes that’s not a good thing but more often than not it has helped me build long lasting, deep and loyal relationships. I believe in legacy. I believe in leaving something behind that has impact and not just in the visual sense. I am a serial committer even if it means I am the last one in the room. I believe in speaking things into being. I’m not religious, but I believe in doing the right thing.

Collaboration and community is at the core of my practice as a result of all of these things. Attempting to go above and beyond a single act to actually drive change in a way that others can access, experience and feel.

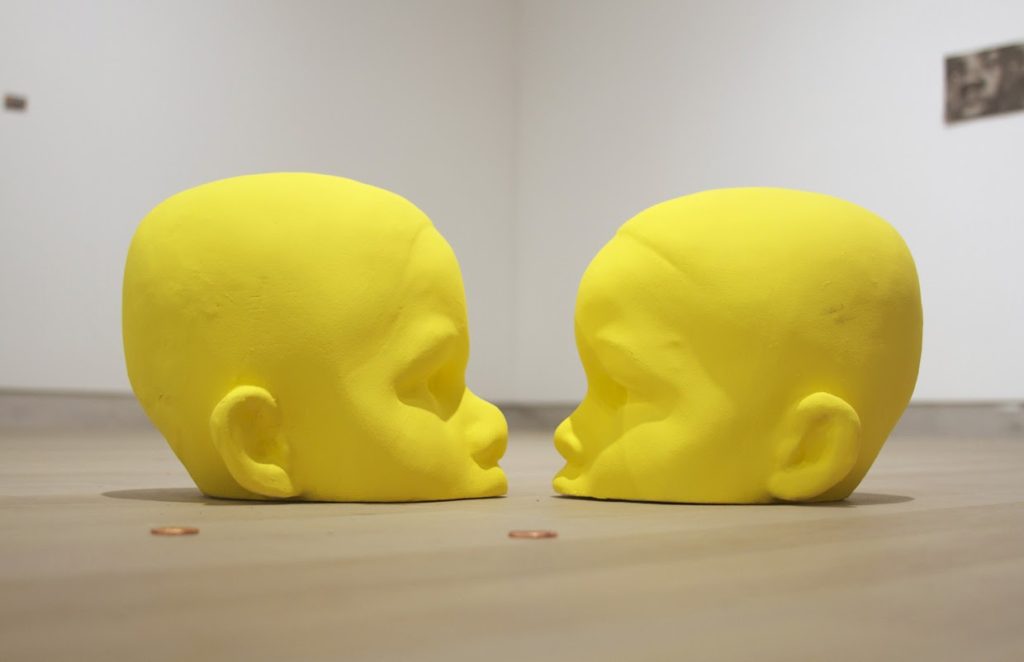

The work I create is dictated by the message I am attempting to communicate. People, space, industrial materials, found objects and my foundation of welding metal have all been leveraged in my work with strong aesthetic around use and wear. I like to feel that people can see what I put into my work rather than just seeing a beautiful object. I want them to connect to its patina, use, and history so that it takes more than one glance to really answer the question of its beauty.