EMERGENCE: Intersections at the Center spotlights The South Side Community Art Center’s historical role in supporting a full spectrum of Black artists through an intersectional viewpoint. The first exhibition of its kind at the South Side Community Art Center, EMERGENCE positions the Center as an important anchor for Black LGBTQ artists who belonged to its community from its founding in 1940 to the 1980s. The exhibition features works addressing identity and community, queer spaces and performance, in collage, painting, sculpture, photography, and more.

EMERGENCE: Intersections at the Center spotlights The South Side Community Art Center’s historical role in supporting a full spectrum of Black artists through an intersectional viewpoint. The first exhibition of its kind at the South Side Community Art Center, EMERGENCE positions the Center as an important anchor for Black LGBTQ artists who belonged to its community from its founding in 1940 to the 1980s. The exhibition features works addressing identity and community, queer spaces and performance, in collage, painting, sculpture, photography, and more.

EXHIBIT

The exhibition is laid out in four sections: EARLY YEARS, NIGHTLIFE, PERFORMANCE, IDENTITY, MIXED MEDIA AND STILL LIFE, and OBLIQUE BODIES. It also includes historical ephemera of interest. Each section page contains a description of the themes represented there and information about the artworks exhibited in that section.

EARLY YEARS

The earliest decades represented in EMERGENCE tell a story of migrations. Richmond Barthé and William Carter traveled to Chicago from Missouri. Charles Sebree and Ellis Wilson came from Kentucky. Allen Stringfellow came from Champaign, Illinois. Of the artists in this early generation, only Berry Horton was born in Cook County. The others were drawn…

Nightlife,

Performance,

Identity

Artists connected to the South Side Community Art Center were also part of intersecting communities that found homes and modes of self-expression in different spaces in the city. The Center’s own Artists and Models Balls involved playful displays that could embrace gender performance and ambiguity, and advertisers included gay bars and bars that featured…

Mixed Media &

Still Life

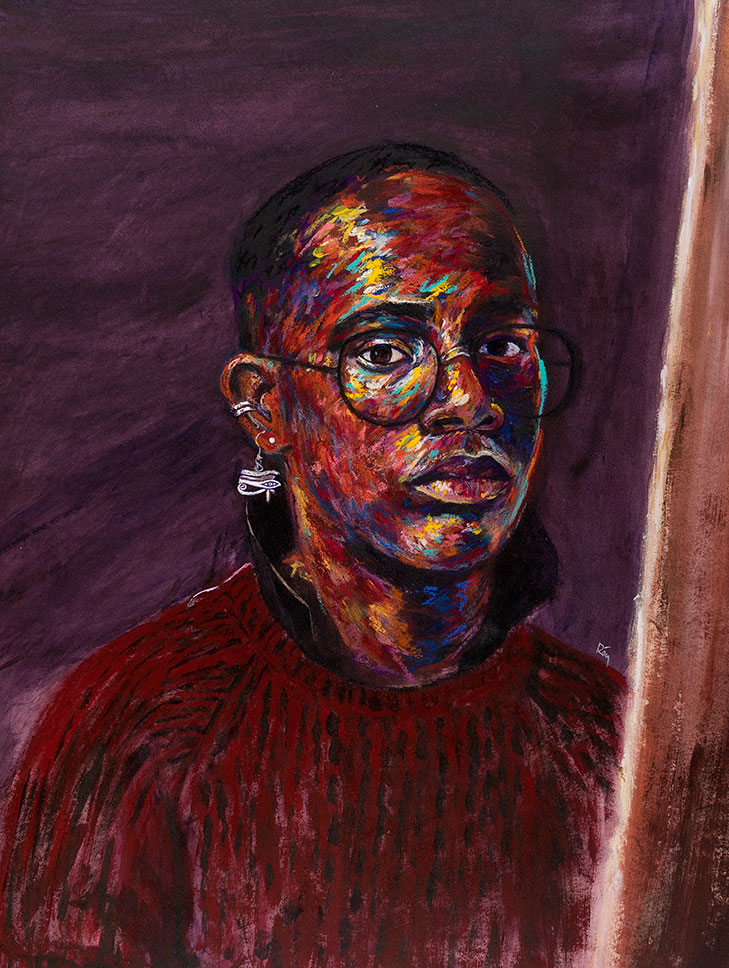

Works in EMERGENCE are diverse in their subject matter and media, but a few themes reappear throughout. Working in abstraction or in the traditionally peaceful genre of still life, artists like William Carter, Allen Stringfellow, and Jonathan Green express themes of interiority or sociability, history or modernity. Notably, Stringfellow and Ralph Arnold both experimented with media …

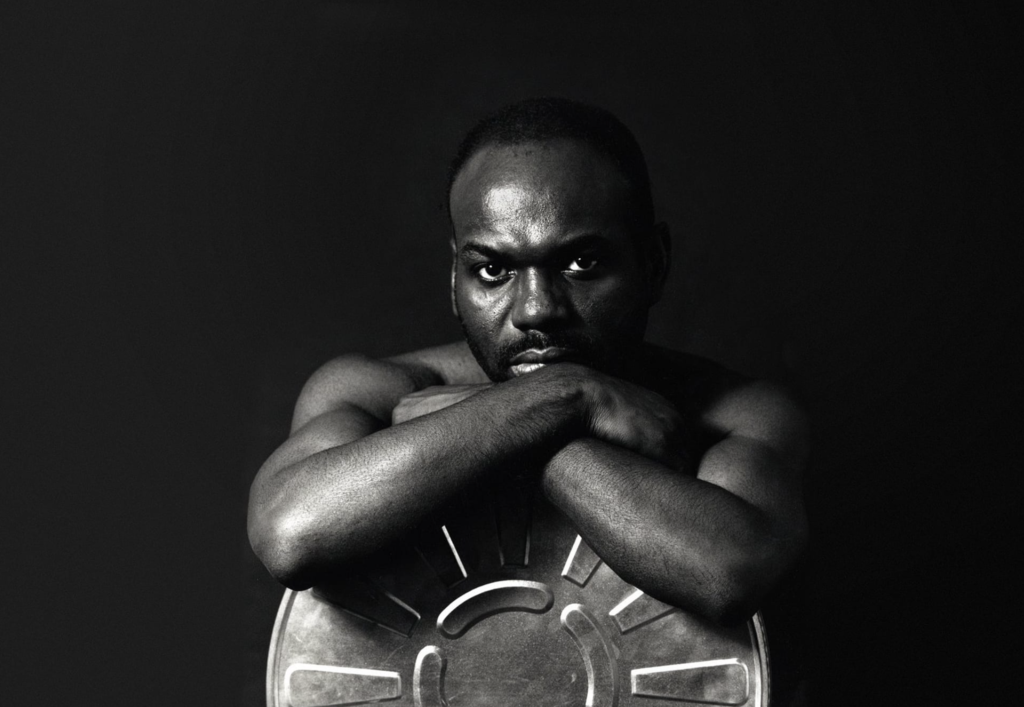

Oblique Bodies

Works in EMERGENCE take part in the long tradition of representing the human form in art, and within that tradition they represent multiple different approaches. The depiction of the body might serve to express something about an artist’s sexuality, or identity—or it might serve very different purposes. The artists in EMERGENCE have multifaceted identities, and approach their work with many different…

ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES

Biographies authored by Gervais Marsh present an overview of the lives of artists in the exhibition

Curatorial Essays

Essays by the exhibition curators, zakkiyyah najeebah dumas o’neal and LaMar R. Gayles, Jr., provide particular insights into two of the featured artists, MIKKI FERRILL and BERRY HORTON.

AIN’T DONE TRYIN YET: ON FERRILL’S GAZE

by zakkiyyah najeebah dumas-o'neal

Exhibition Curator, Manager of Public Engagement and Programs

CALL ME BY MY NAME – TELL ME IN PRIVATE: THE PRACTICE OF BERRY HORTON

by LaMar R. Gayles, Jr.

Exhibition Curator, Archives and Collections Manager

History & Resources

EMERGENCE emphasizes the middle decades of the twentieth century, from the 1940s to the 1980s. For much of this time period, sexual orientation was heavily policed, both literally by the Chicago Police Department, and in a variety of other ways through the imposition of norms by society and its institutions, such as church, family, medical institutions, and school. For this reason, many of the artists in the exhibition, especially in the early decades represented here, were careful to exercise discretion in their life and work. Most did not publicly identify themselves as gay, lesbian, trans, or bisexual. At the same time, particularly in Bronzeville, Chicago’s South Side Black community held spaces that were open to participants of differing sexual orientations and identities. And political movements on behalf of Gay Liberation were active throughout this period, gaining strength in the 1970s and 80s.

Historical research reveals that many artists affiliated with the Center, even in its early decades, had romantic and sexual lives that included same-sex partners and desires. Whether this experience is visible in their work is another question entirely—one that we open up to our audience to help us consider, rather than making conclusive claims about it.

Alongside artists who might today identify as LGBTQIA+, EMERGENCE includes artists who depict spaces and performances that were part of the South Side’s queer life, or who collaborated with, influenced, or inspired other artists in the exhibition, without themselves necessarily being queer-identified.

More information about the artworks and historical documents exhibited in EMERGENCE can be found in the checklist and ephemera lists linked here. A syllabus by Gervais Marsh provides an introduction to the way historians and art historians have studied this material, providing historical context for the exhibition and a wealth of related ideas, images, documents, and questions for discussion.

Links & Downloads

CHECKLIST of all the artworks displayed in the exhibition

EPHEMERA list of historical documents and sketches in the exhibition

INTERVIEWS (Coming soon)

EXHIBITION EVENTS

NEWS

CALL ME BY MY NAME – TELL ME IN PRIVATE: THE PRACTICE OF BERRY HORTON

Call Me By My Name – Tell Me In Private: The Practice of Berry Horton LaMar R. Gayles, Jr. In the song “MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name),” musician Lil

CREDITS

Major support for EMERGENCE was provided by a Terra Foundation Re-Envisioning Permanent Collections grant. Programming support is provided by Northwestern University Mary Jane Crowe Program funds.

Special thanks to South Side Community Art Center Executive Director Monique Brinkman-Hill for her unwavering support of this project; to Heidi Marshall at Columbia College Library for facilitating archival research; lenders to the exhibition, including the Bates College Museum (Dan Mills and Corie Audette); the Block Museum (Kathleen Bickford Berzock, Janet Dees, Dan Silverstein, Joe Scott, and Kristina Bottomley); the Aaron Gallery (Patrick Albano and Lynne Schillaci); and Juarez Hawkins, Patric McCoy, and Margaret R. Vendryes and Jacqueline Herranz-Brooks. Additional thanks to Zahra Glenda Baker, Simone Bouyer, Chad Heap, Brian Leahy, Solveig Nelson, Michael W. Phillips, Jr., Gregory Sykes, and the Columbia College Department of Exhibitions.

Many thanks to The Woodshop and Block Museum for framing, to Faye Wrubel and the Graphic Conservation Company for conservation treatment paintings and works on paper respectively, and to Tony Smith for expert photography.

Exhibition Staff and Advisors

Exhibition curators: zakkiyyah najeebah dumas-o’neal and LaMar R. Gayles, Jr.

Curatorial researcher: Gervais Marsh

Curatorial intern: Chantel McCrea

Exhibitions manager: Lola Ogbara

Project advisor and editor: Rebecca Zorach

Publication designer: Aay Preston-Myint

Web design: That’s So Creative

Exhibition board of advisors: Kemi Adeyemi, Tristan Cabello, Aymar Jean Christian, Gregory Foster-Rice, Juarez Hawkins, Patricia McCombs, Patric McCoy, Shanta Nurullah, Margaret R. Vendryes

In Memoriam

In the final weeks of preparation for EMERGENCE, we learned of the passing of the artist and art historian Dr. Margaret Rose Vendryes (1955–2022). Margaret was an enthusiastic and early supporter of this exhibition project and generously offered her vast knowledge of early twentieth–century African American artists as a project advisor who also loaned a work in her personal collection (Richmond Barthé’s St. Sebastian) to the exhibition. We join with all who loved her in mourning her loss, we celebrate the legacy of her art and scholarship, and we express deep gratitude for the contributions that immeasurably enriched EMERGENCE.